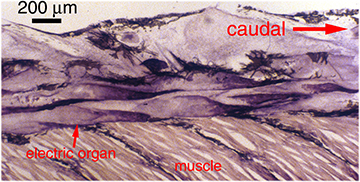

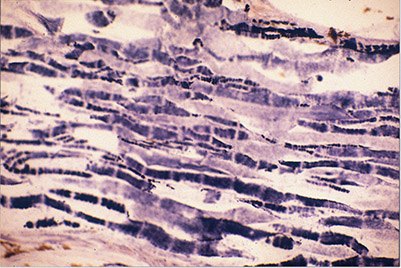

Electric organs Electric organs evolved independently in several groups of fishes — electric skates (Torpedo), electric rays (Raja), strongly electric catfish (Malapterurus), weakly electric catfishes (Synodontis spp.), stargazers (Astroscopidae), South American knifefishes (Gymnotiformes), and African mormyriform fishes (reviewed in Bass 1986; Moller 1995). In most electric fish, the electric organ is derived from muscle (see below). Electrocytes, the cells that comprise muscle-derived electric organs, retain some of the electrical properties of muscle, but have lost their contractile properties (Bennett 1971a).

The electric fish that we study in our lab, South American ghost knifefish (family Apteronotidae), are exceptional in that their electric organs are derived from nervous tissue, rather than muscle. The electric organ of apteronotid fish consists of bundles of hypertrophied axons of spinal electromotor neurons. These axons synchronously and rhythmically produce action potentials to generate a high-frequency, oscillating (AC) electrical field around the fish.

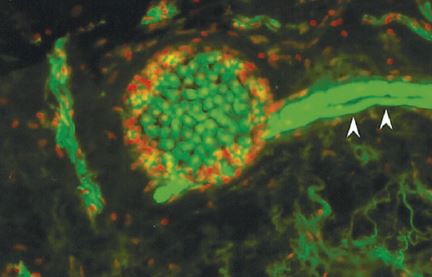

Electroreceptors The ability to detect bioelectric fields is a primitive trait in vertebrates, but was lost in teleost fish, and then independently re-evolved in several different teleost lineages. Electrical fields are detected with specialized electroreceptor organs in the skin. Electroreceptors in species that lack electric organs (e.g. sharks, lampreys, catfishes) are ampullary receptors that are specialized for passively detecting the very weak bioelectric fields produced by other organisms. To detect such weak electric fields, ampullary receptors must be very sensitive and accomplish this by temporally integrating electric fields. As a consequence of their extreme sensitivity, ampullary receptors respond primarily to low-frequency signals and are relatively insensitive to high-frequency signals.

Weakly electric fish (South American gymnotiform knifefish and African mormyriform fish) also have ampullary receptors, but have evolved additional classes of receptors (e.g., tuberous receptors in gymnotiform fishes) that are tuned to higher frequency electrical signals and are specialized for active electrolocation and communication (Bennett 1971b).

Cited References

- Bass AH. 1986. Electric organs revisited: evolution of a vertebrate communication and orientation organ. In: Bullock TH, Heiligenberg W, editors. Electroreception. New York: Wiley. p 13-70.

- Bennett MVL. 1971a. Electric organs. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. Fish Physiology. New York: Academic Press. p 347-491.

- Bennett MVL. 1971b. Electroreception. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. Fish Physiology. New York: Academic Press. p 493-574.

- Moller P. 1995. Electric fishes: history and behavior. London: Chapman & Hall. 584.

- Smith, G.T., Unguez, G.A., and Reinauer, R.R., Jr. 2001. NADPH-diaphorase activity and nitric oxide synthase-like immunoreactivity colocalize in the electromotor system of four species of gymnotiform fish. Brain, Behav., Evol. 58:122-135.

- Smith, G.T., Unguez, G.A., and Weber, C. 2006. Distribution of Kv1-like potassium channels in the electromotor and electrosensory systems of a weakly electric fish. J. Neurobiol. 66:1011-1031.