The Jamming Avoidance Response (JAR) and Long-term Frequency Elevations (LTFE)

Electric fish detect nearby objects by analyzing how the objects perturb the amplitude and timing of their EODs. When two electric fish are near each other, their EODs may interfere with each other and disrupt their ability to electrolocate. This disruption is greatest when the EOD frequencies of the fish are close to each other (i.e., 4-20 Hz apart). Many species of electric fish express a reflexive behavior called the jamming avoidance response (JAR, Heiligenberg, 1973). The fish that has the higher EOD frequency will raise its EOD frequency away from that of the other fish. In some species, the fish with the lower EOD frequency will decrease the frequency of its EOD (Heiligenberg et al. 1996).

Our lab has found that JARs and the stimuli that elicit them can vary substantially both across individuals within species and across species (Ho et al., 2010; Petzold et al. 2018; Freiler et al. 2022). In some cases, fish produce JAR-like behaviors in which they increase their EOD frequencies in response to other EODs whose frequencies are far away from their own, and thus less likely to jam their electrolocation abilities. These findings suggest that JARs might function in communication as well as in electrolocation.

If the jamming EOD is transient, the EOD frequency will return to its baseline after the jamming EOD is removed. If a fish is exposed to a jamming EOD for a long period of time, however, the frequency of the EOD may remain elevated even after the jamming EOD is removed (Oestreich and Zakon 2002). This behavior is known as a long-term frequency elevation (LTFE), which may function to allow fish to avoid jamming when they are in stable social groups.

Chirps and Rises

When electric fish interact, they often rapidly modulate both the frequency and amplitude of their EODs to produce communication signals that have been called pings, chirps, rises, interruptions, rasps and yodels. Chirps and rises are the most common EOD modulations.

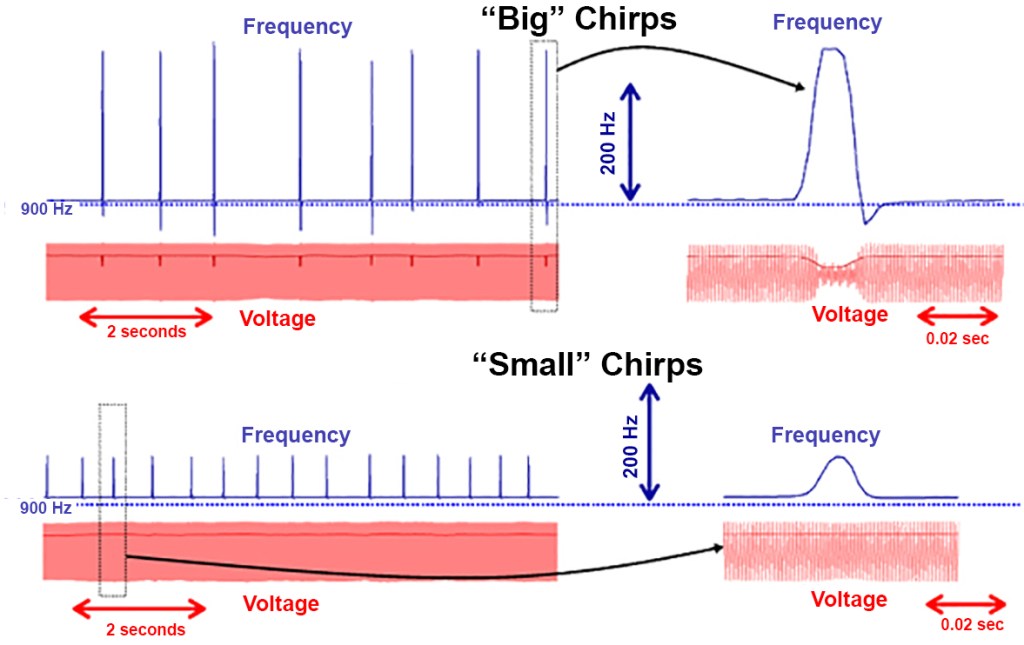

When fish chirp, they typically increase their EOD frequency by tens to hundreds of Hz and decrease EOD amplitude for tens to hundreds of milliseconds. The parameters of chirps vary substantially both within and across species and are often produced when fish are interacting aggressively or during courtship. Chirps that have a lot of frequency modulation (i.e., in which EOD frequency increases a lot) also have more amplitude modulation (i.e., EOD amplitude decreases more). Very short chirps that have a lot of frequency modulation also end with a “frequency undershoot” in which EOD frequency drops below its baseline at the end of the chirp.

Chirping has been most extensively studied in the brown ghost knifefish (Apteronotus leptorhynchus). Chirping is highly sexually dimorphic in this species. Male brown ghosts chirp 10-20 times more often than females. These fish also produce distinct types of chirps: “Small” chirps, in which EOD frequency rises ~30-100 Hz above its baseline; and “Big” chirps, in which EOD frequency rises 150-400 Hz above its baseline. Both sexes produce small chirps, but big chirps are produced primarily by males. Furthermore, small chirps are produced most in response to the EODs of same-sex fish, whereas males produce more big chirps in response to female EODs. These findings have led to the hypothesis that small chirps are agonistic signals and big chirps are courtship signals.

The function of rises is less well-studied than that of chirps. The production of rises differs less across sexes than that of chirps. Rises have less frequency modulation (FM) and/or longer duration than chirps, and although the duration and FM of rises varies a lot, rise duration and FM are correlated — rises that have very little FM (a few Hz) are very short (a few milliseconds), whereas rises with more FM (up to tens of Hz) are much longer in duration (up to tens of seconds). The structure of rises also varies much less across species than that of chirps.

References

Freiler, M.K., Proffitt, M.R., and Smith, G.T. 2022. Electrocommunication signals and aggressive behavior varies among male morphs in an apteronotid fish, Compsaraia samueli. J. Exp. Biol. 225:243452.

Heiligenberg, W. 1973. “Electromotor” response in the electric fish Eigenmannia (Rhamphichthyes, Gymnotoidea). Nature 243:301-302.

Heiligenberg, W., Metzner, W., Wong, C.J.H., and Keller, C.H. 1996. Motor control of the jamming avoidance response of Apteronotus leptorhynchus: evolutionary changes of a behavior and its neural substrate. J. Comp. Physiol. A 179:653-674.

Ho, W.W., Fernandes, C.C., Alves-Gomes, J.A., and Smith, G.T. 2010. Sex differences in the electrocommunication signals of the electric fish Apteronotus bonapartii. Ethology 116:1050-1064.

Oestreich, J. and Zakon, H.H. 2002. The long-term resetting of a brainstem pacemaker by synaptic input: a sensorimotor adaptation. J. Neurosci. 15:8287-8296.

Petzold, J.M., Alves-Gomes, J.A., and Smith, G.T. 2018. Chirping and asymmetric jamming avoidacne responses in the electric fish Distocyclus conirostris. J. Exp. Biol. 221:178913.