Because EOD frequency and chirping vary systematically within and between species, these signals can convey information about species identity, sex, reproductive condition, dominance, and/or motivation. How receivers use chirps and EOD frequency to evaluate conspecifics, however, is only partly understood. One of the main projects in our laboratory is to understand how fish respond to different types of electrocommunication signals.

We use several different approaches to assess the functions of EOD frequency and chirping in several different apteronotid species that differ in the degree and direction of sexual dimorphism in these signals:

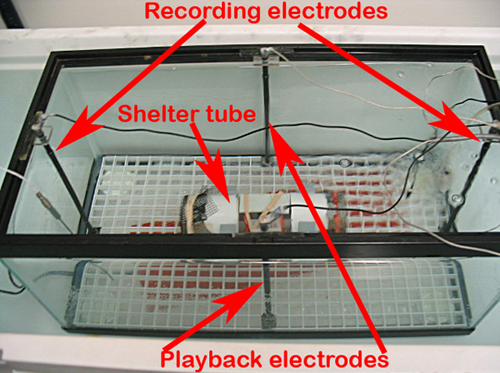

(1) Playbacks of simulated electrocommunication signals to fish in a “chirp chamber.” One way in which we study the function of EODs and chirping is to record the responses of fish to playbacks of simulated EODs in a chirp chamber. The fish is placed in a shelter tube on the bottom or a tank or in a net “hammock” suspended in a tank with recording electrodes placed at the ends of the tank opposite the head and tail of the fish and playback electrodes placed on the other two sides of the tank. We can vary the frequency of the stimulus to simulate the presence of a fish of the same or opposite sex, a fish with a higher or lower EOD frequency (which in some species is an indicator of dominance or subordinance), or a fish of the same or different species. Most fish respond to playbacks by chirping. Indeed, some fish produce more than a hundred chirps during a two-minute playback. An advantage of using a chirp chamber is that because the fish, recording electrodes, and stimulus electrodes are in a fixed orientation, we can use relatively simple algorithms to isolate the subject fish’s EOD from the playback stimulus. This allows us to use customized software to precisely measure structural parameters of chirps (i.e. the amount of frequency modulation, duration, and amplitude modulation). This method thus allows us to compare how the structure of chirps of different species and sexes are affected by different types of social stimuli (Turner et al. 2007).

(2) Playbacks of electrocommunication signals to freely-swimming fish. Chirp chamber experiments allow us to precisely quantify the structure of chirps and other electrocommunication signals. Because fish in the chirp chamber remain in the recording tube or net hammock during the playback, the recording configuration is not very naturalistic, and we are unable to use this technique to study the physical interactions of the fish with different stimuli. To study the range of behaviors that accompany electrocommunication signals, we use infrared-sensitive video cameras to record the behavior of freely-swimming fish interacting with playback stimuli or with the EODs of fish in an adjacent tank. We use this technique to study how the EODs and chirping of other fish affect aggression and courtship behavior.

(3) Recording EODs and behavior of freely interacting fish. We also use electrode arrays and infrared video recording to analyze electrical signals and other behaviors. Although it is difficult to analyze the fine structure of chirps using this method, it allows us to examine how fish chirp in semi-natuarlistic social contexts. For example, we can determine whether dominant fish chirp more than subordinate fish and quantify behaviors that fish perform before and after they chirp or are chirped at.

We use these experimental techniques to address the following questions:

What information is conveyed by EOD frequency?

Do males and females (or fish of different species) respond differently to playbacks male vs. female EOD frequencies or to same-sex EODs with frequencies higher versus lower than the fishes’ own EOD? For example, both brown ghost knifefish and black ghost knifefish both produce two different types of chirps (high-frequency chirps and low-frequency chirps). By examining the stimuli that elicit these chirps, we found that the social context in which different types of chirps are produced differs between species. Males and females in both species produce low frequency chirps most often during same-sex interactions. In brown ghosts, however, high frequency chirps are produced mostly by males in response to female EODs, whereas in black ghosts both sexes produce high frequency chirps mostly in response to same-sex EODs (Kolodziejski et al. 2007). These results suggest that the function of analogous signals has changed in closely-related species.

What are the function of chirps and rises?

Do males and females (or fish of different species) respond differently to chirping versus non-chirping EODs? Do they respond differently to different types of chirps? Does the condition of the fish (reproductive condition, dominance status) influence how a fish chirps or responds to chirps? Do fish chirp more or less (or produce different types of chirps) at different times of day/night? Do fish behave more aggressively when they chirp or are chirped at? Do fish chirp back and forth at each other with “echo responses?” By correlating the behaviors fish perform before and after they chirp as well as the social, physiological, and physical contexts in which they chirp during live interactions, we are elucidating the meaning and function of chirps and other EOD modulations.

References

Kolodziejski, J.A., Sanford, S.E., and Smith, G.T. 2007. Stimulus frequency differentially affects chirping in two species of weakly electric fish: implications for the evolution of signal structure and function. J. Exp. Biol. 210:2501-2509.

Turner, C.R., Derylo, M., de Santana, C.D., Alves-Gomes, J.A., and Smith, G.T. 2007. Phylogenetic comparative analysis of electric communication signals in ghost knifefishes (Gymnotiformes: Apteronotidae). J. Exp. Biol. 210:4104-4122.