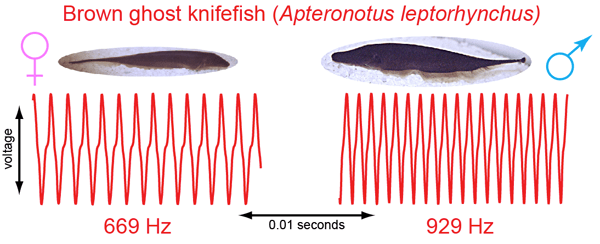

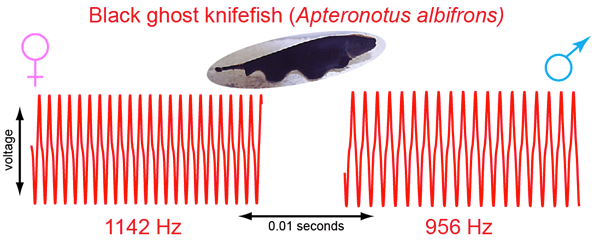

In many species of electric fish, EOD frequency (the rate at which the fish discharges its electric organ) differs between males and females. Both the magnitude and the direction of sex differences in EOD frequency vary across species.

In the brown ghost knifefish (Apteronotus leptorhynchus), males discharge their electric organs at higher rates than females. Adult male A. leptorhynchus EODs are typically emitted at frequencies of 800-1050 Hz, whereas females typically have EOD frequencies of 600-750 Hz.

In some populations of the black ghost knifefish (Apteronotus albifrons), EOD frequency is also sexually dimorphic, but the direction of the sex difference is reversed compared to that in A. leptorhynchus. Males have significantly lower EOD frequencies than females. Male EODs are emitted at frequencies of 850-1000 Hz, whereas female EOD frequencies are typically 1000-1150 Hz. Our laboratory discovered that in other populations of black ghost knifefish, EOD frequency does not differ between the sexes (see our research page for more details).

Hormonal regulation of EOD frequency. Sex differences in EOD frequency are regulated by androgens (e.g., 11-ketotestosterone, 11-KT) and in some cases estrogens. The effects of androgens on EOD frequency is reversed in brown ghost vs. black ghost knifefishes (Dunlap et al. 1998). In brown ghosts, 11-KT masculinizes EODs by increasing their frequency. 11-KT also masculinizes EODs in sexually dimorphic populations of black ghost knifefishes, but since male black ghosts have lower EOD frequencies in females, 11-KT decreases, rather than increases, EOD frequency. Our lab is particularly interested in the endocrine, molecular, and evolutionary mechanisms that underlie these reversals in sexual dimorphism.

Sexually monomorphic EODs. In some other knifefish species, including pig-duck knifefish (Parapteronotus hasemani), dragon knifefish (‘Apteronotus’ bonapartii), and overo knifefish (Adontosternarchus spp.), EOD frequency is sexually monomorphic and does not differ between males and females (Ho et al., 2010; Petzold and Smith, 2016; Zhou and Smith, 2006). Populations can also vary in the degree of sexual dimorphism in EODs. In black ghost knifefish, some populations have sexually dimorphic EOD frequency, whereas other populations have little or no sex differences (Ho et al., 2013). Although less is known about hormonal regulation of EOD frequency in species and populations that lack sex differences in their EODs, the studies that have been done suggest that EOD frequency is unresponsive to androgens and/or estrogens in these species and populations. Our laboratory also investigates the mechanisms that underlie gains and losses of sexual dimorphism of EODs.

References

Dunlap, K.D., Thomas, P., and Zakon, H.H. 1998. Diversity of sexual dimorphism in electrocommunication signals and its androgen regulation in a genus of electric fish, Apteronotus. J. Comp. Physiol. A 183:77-86.

Ho, W.W., Fernandes, C.C., Alves-Gomes, J.A., and Smith, G.T. 2010. Sex differences in the electrocommunication signals of the electric fish Apteronotus bonapartii. Ethology 116:1050-1064.

Ho, W.W., Rack, J.M., and Smith, G.T. 2013. Divergence in androgen sensitivity contributes to population differences in sexual dimorphism of electrocommunication behavior. Horm. Behav. 63:49-53.

Petzold, J.M. and Smith, G.T. 2016. Androgens regulate sex differences in signaling but are not associated with male variation in morphology in the weakly electric fish Parapteronotus hasemani. Horm. Behav. 78:67-71.

Zhou, M. and Smith, G.T. 2006. Structure and sexual dimorphism of the electrocommunication signals of the weakly electric fish Adontosternarchus devenanzii. J. Exp. Biol. 209:4809-4818.